Afro-Cuban History is Integral to Hispanic Heritage. Here’s Why.

Understanding Hispanic Heritage Month digs deep into the rich cultural and ethnic roots of a people whose ancestry hails from many continents. With that in mind, ProgressReport.co commissioned Cuban writer and University of Texas San Antonio History Professor Jorge Felipe-Gonzalez, a scholar of Afro-Cuban history, to provide educational resources on Afro-Cuban heritage.

The day I turned 14, I was admitted to one of Havana’s pediatric hospitals for meningitis. My head felt like a giant nest filled with jumpy needles. I had a high fever, nausea, and my bones ached with every movement. Twice a day, the nurse administered me antibiotics through an IV attached to my arm. But the treatment wasn’t working, and the doctors advised my family to brace for the worst.

Most of the time, I was lethargic to the point of stupor, but I recall the night when a man entered the room fully dressed in white with long, multicolored beaded beads dangling around his neck. He was a Babalawo, a Yoruba priest that my grandmother had summoned to heal me.

Keep up with the latest from UnidosUS

Sign up for the weekly UnidosUS Action Network newsletter delivered every Thursday.

“The boy is cursed with the evil eye,” he said. He treated me by rubbing a chicken egg over my legs and arms, spraying rum from his mouth onto my whole body, and sung in a language I could not understand. The following morning, my fever had vanished, leaving me to wonder what cured me— the antibiotics or the priest?

Fervent Catholic and white of Spanish descent as my grandmother was, she believed in the spiritual powers of Afro-Cuban religions. Others in my family shared that faith. My grandfather, for example, had a shrine dedicated to Eleggua, the Orisha deity of the crossroads, which he kept in his bedroom next to a an iron Holy Cross. To this day, my mother updates me about her latest visits to her santero friend, who predicts upcoming life events and warns her about hidden dark forces.

For extraordinary as those stories might seem, they are not the peculiar adventures of an unconventional family. Afro-Cuban religions are everywhere in Cuba, crossing racial, class, and faith lines. Fidel Castro, to mention a well-known Cuban, was called, among other epithets, El Mayimbe, a Palo Monte spiritual figure represented by a black vulture that communicates directly with God. Every January 1 in Havana, the Yoruba Cultural Association issues the much-awaited letter of the year that forecasts the island’s future. This 2021, one prediction was an “increased contempt for authority.” On July 11, nationwide protests unfolded across Cuba reaching proportions not seen in decades. They were largely led by Afro-Cuban artists attempting to hold the revolution accountable for its promises of creating equal opportunities for all, while demanding more freedom of expression, assembly, and political representation.

When Cubans migrate, they carry their spiritual worldviews and adapt them to foreign environments. Yelp, for example, lists the best santeria places in Miami, the epicenter city of Cuban migrants in the United States. Not too long ago, the Miami Herald published a curious story about a man who stumbled across a cow tongue rotting at the bottom of an old-growth tree while he was jogging in Miami’s Tropical Park. In Cuba, it is common for believers to place offerings at the feet of every Ceiba, a majestic tree of a thick and tall truck that is sacred for the Rule of Osha or Santeria.

“Dead chickens, roosters, pigeons, goats, pigs — and anatomical parts thereof —,” noted the article, “have been found atop the hill that is popular with people who like to exercise in Tropical Park.”

The African legacy goes beyond the religious realm. The foods Cubans enjoy the most, our typical cuisine, is made of autochthonous African ingredients such as okra, yam, plantain, or malanga root. Cuban music owes its existence to African instruments such as the batá, iyesá, and bembé drums or the güiro. World-known Cuban rhythms such as rhumba, conga, salsa, and son cubano are the ultimate result of the African heritage blending with Spanish and other beats. Our everyday Spanish language has been enriched by African words such as fula, ampanga, guaguancó, or bachata. Cubans themselves are, as recent DNA studies prove, partially Africans.

But Cuba’s expression of African culture evolved primarily as a mechanism of existential survival and adaptation for the African men and women that experienced slavery, dehumanization, and racism on the island for 350 years. Against all the odds, the harrowing experience of enslavement, the racial structures in which the system rested, and the everyday acts of violence it entails did not erase it.

A vast body of scholarship and artistic expressions have reflected upon the creation of Afro-Cuban culture and the Black experience in the island’s history. As a Cuban, I am part of that culture which has become my research subject for years. In what follows, I share some of my favorite books, films, and other media resources that can help educators and students learn about that history.

Educational Resources:

The transatlantic slave trade was the starting point of the African presence in the New World. Around 12.5 million Africans were enslaved and brought to the Americas. About a million of them ended in Cuba, more than double the 400,000 who came to the United States. If you are interested in this history, the digital site The Transatlantic Slave Trade Database contains a trove of information on nearly 40,000 slave ships that users can search and filter. It also includes dynamic maps, a 3D visualization of a slave ship, syllabi, and digitized records. This popular site has been featured in scholarly literature and national outlets such as The New York Times.

When it comes to the early presence of Africans in Cuba, meaning during the 16th and 17th centuries, our knowledge is incomplete. Archival sources are scarce compared to later years, and Cuba was not a major destination for Africans. There is a book I highly recommend entitled Havana and the Atlantic in the Sixteenth Century by Cuban-American Harvard professor Alejandro de la Fuente. It recreates the time when the city of Havana was in the making and Africans from today’s countries of Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Angola were cementing what centuries later became the richest Caribbean metropole.

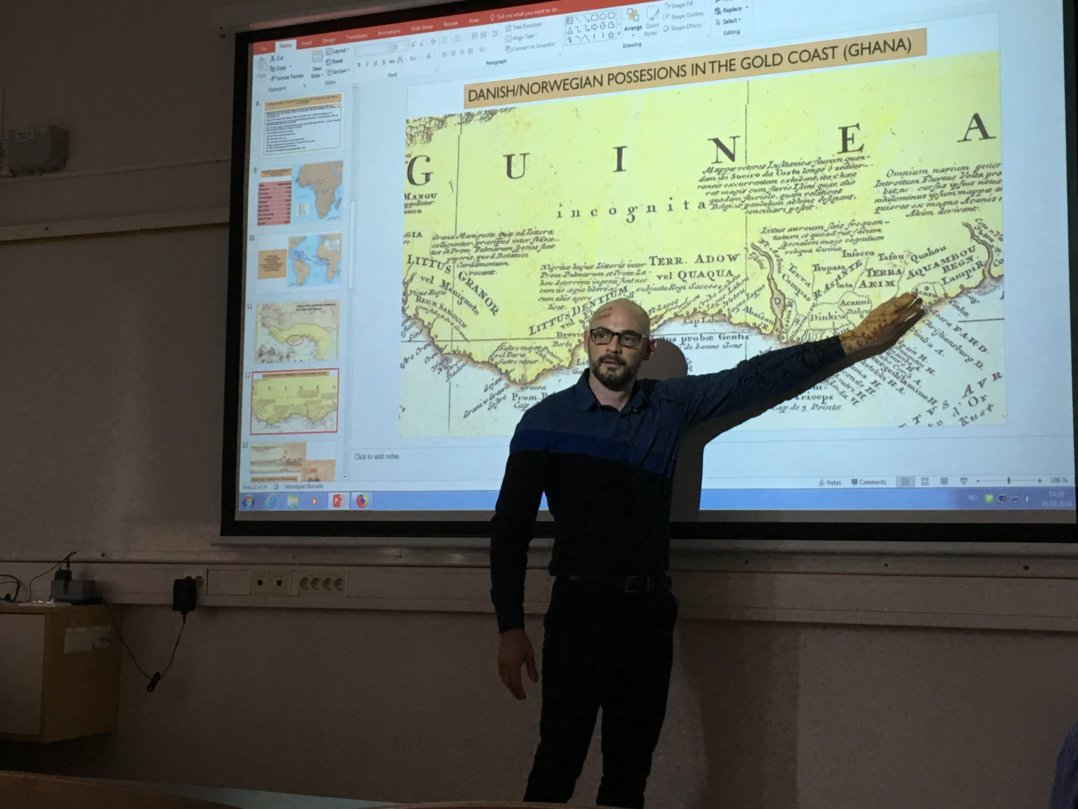

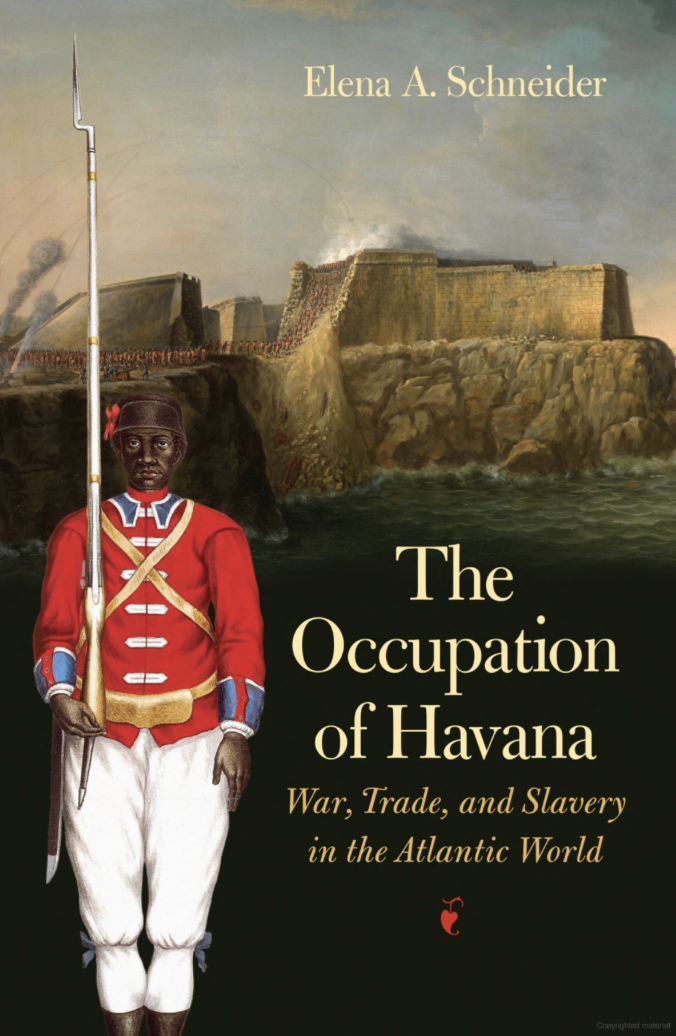

By the mid-18th century, the profitable sugar industry made inroads in the hinterland of Havana. As a result, the number of slaves grew in a matter of decades. Historian Elena Schneider recently published The Occupation of Havana: War, Trade, and Slavery in the Atlantic World, in which she explores the expansion of sugar production in Cuba and the subsequent growth in slave trading activities that occurred after the British occupied Havana for a few months in 1762.

In the 1800s, Cuba became a full-fledged slave-trading colony, with sugar production surpassing global competitors. In that century, the African presence was more visible than ever. Also, it was when the most important slave rebellions occurred, and slavery was finally abolished.

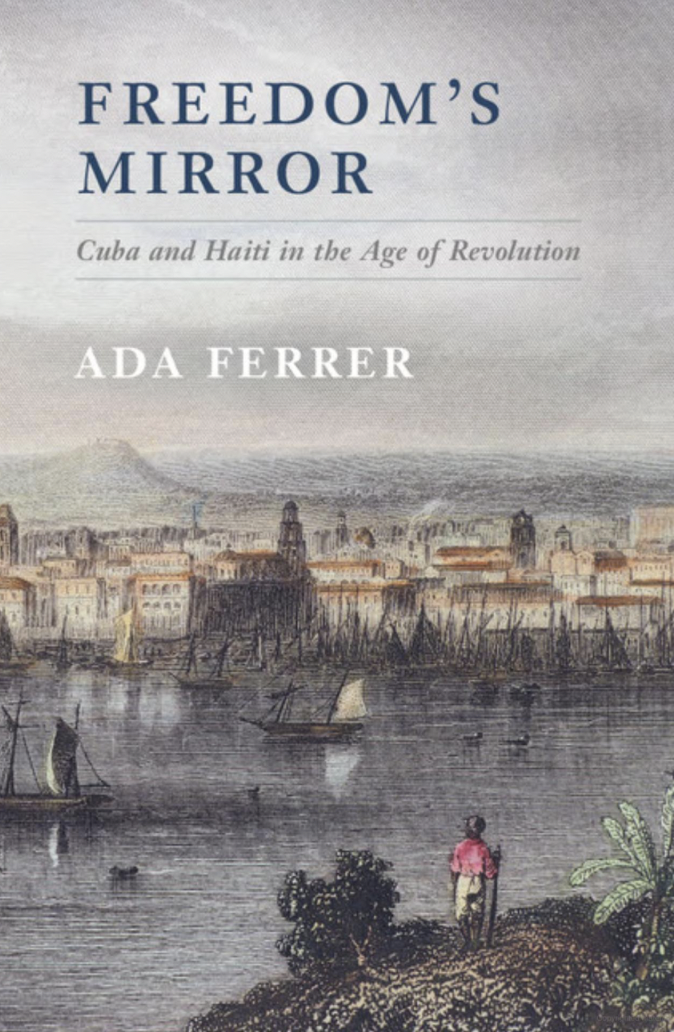

A classic monograph on how the entire plantation system worked is The Sugarmill by Cuban historian Manuel Moreno Fraginals. This lucid text is a classic in the historiography of the sugar plantation complex on the island and its human and environmental costs. Freedom’s Mirror: Cuba and Haiti in the Age of Revolution by Cuban American historian Ada Ferrer is a book I’d recommend for understanding Cuba in the early 19th century. With more than a decade of archival research, Ferrer presents a brilliant analysis on how the collapse of the sugar production in Saint-Domingue in the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution (1791) enabled the expansion of the sugar plantation economy in Cuba while turning into a source of inspiration for freedom to those suffering under the yoke of slavery in Cuba.

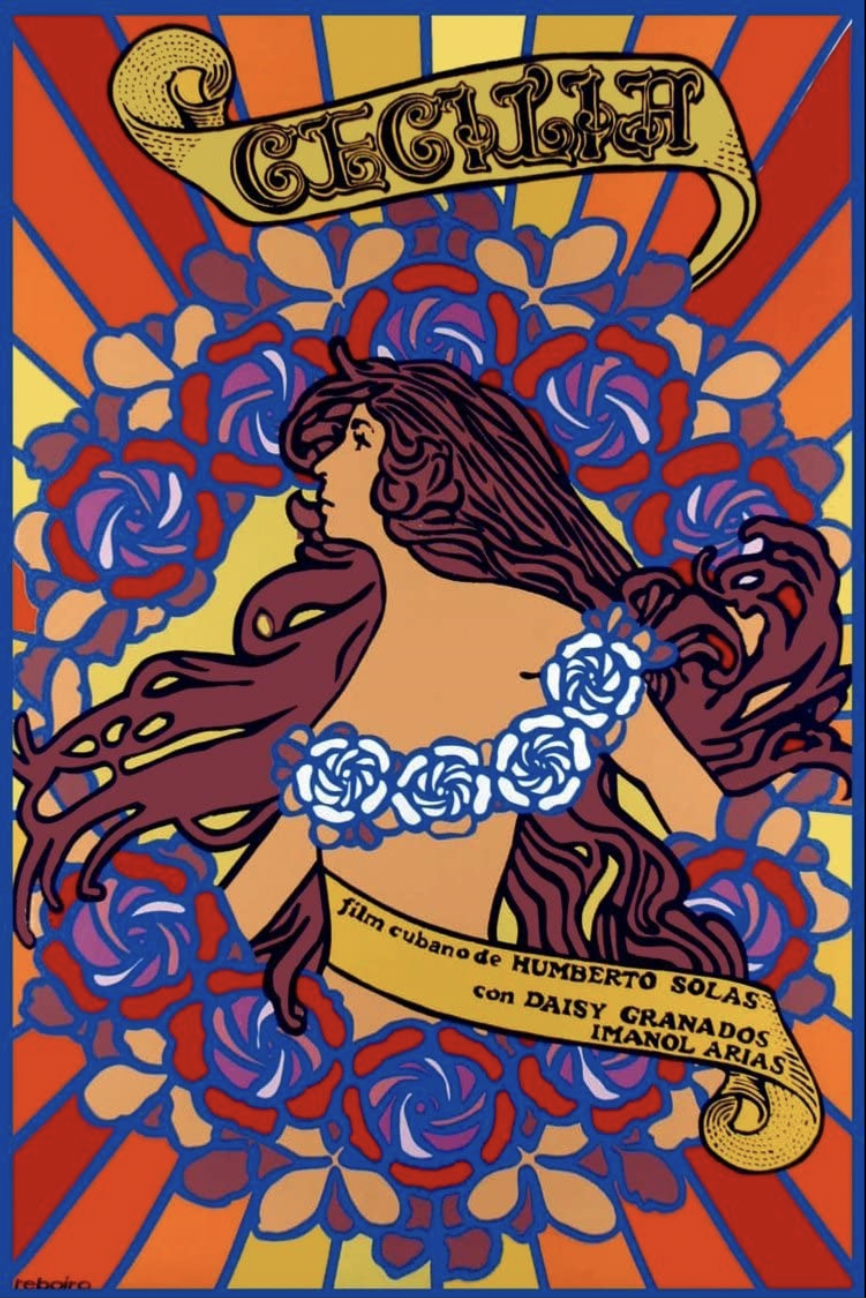

It is a well-studied fact that all across the Americas, enslaved women and men resisted bondage by running away, revolting, and maintaining their cultural traditions alive. Film director Tomás Gutierrez Alea recreates a slave rebellion in late 18th century Cuba in the movie The Last Supper. Another classic of the filmography on 19th-century Cuban slavery is Cecilia by Humberto Solás, based on a similar book by Cirilo Villaverde. The central plot centers on a love affair between a white planter and a free mixed-race woman from Havana and the challenges they faced. But the movie also conveys the spiritual world of Afro-Cubans in the 19th century.

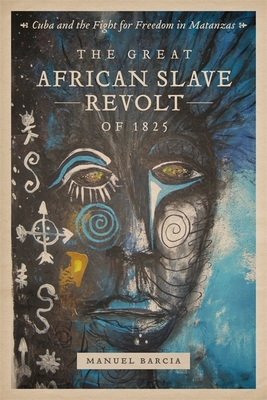

Cuba’s most important Afro-Cuban conspiracies occurred in 1812, led by José Antonio Aponte, a Black freedom fighter of Yoruba origin. Matt Child’s book The Aponte Rebellion describes the plot that intended to overthrow slavery in Cuba. The movement struck some sugar plantations in Havana before being repressed by colonial military forces. Robert L. Paquette’s book Sugar is Made with Blood, describes a slave conspiracy known as La Escalera (1843-44). Afraid of a major slave uprising like the one in Saint-Domingue, colonial officers punished and prosecuted masses of enslaved and freed people of color in Havana. Manuel Barcia’s The Great African Slave Revolt of 1825 linked the 1825 uprising in Matanzas with the African heritage of the rebels and their previous experience as warriors in their homeland.

Unlike the United States, where former slave testimonies are abundant, we rarely find those voices in print in Cuba. There are many reasons for it, but the most important is the absence of a domestic abolitionist movement on the island. One exceptional case of a slave testimony is The Autobiography of a Slave by Francisco Manzano. Two other examples, recorded by anthropologists, are Biography of a Runaway Slave way Slave by Miguel Barnet and Reyita: The Life of a Black Cuban Woman in the Twentieth Century by Maria de los Reyes Castillo. Unfortunately, there are no other biographies written or told by those who experienced slavery and subsequent racism under free labor conditions.

In 1886, Cuba became one of the last regions in the Americas to abolish slavery—Brazil was the latest in 1888. Historian Rebecca Scott wrote one of the more referenced books on the transition from coerced to free labor in Cuba. In Slave Emancipation in Cuba, Scott focuses not only on the abolitionist political debates but also on the everyday actions taken by the slaves and free Black people to erode the system of enslavement from below.

The abolition of slavery was a monumental historical transformation. Yet, it did not result in the immediate improvement in the living conditions of the former captives or their civil equality. Like in the United States, there were racial structures privileging whiteness over Blackness. Unlike the United States, these cultural structures were never codified into segregation laws like Jim Crow. However, there was violence against Afro-Cubans.

In 1912, Afro-Cubans rallied against the primarily white establishment after being denied their right to form a political party. In Our Rightful Share: The Afro-Cuban Struggle for Equality, 1886-1912, historian Aline Helg reconstructs the second-citizen experience of Black Cubans after the abolition of slavery and their struggle to find a political voice. The 1812’s War of the Independents of Color was the biggest massacre against black people in the island’s history. It is estimated that the state killed around 3,000 Black men and women with the support of U.S. military forces.

Race, Inequality, and Politics in Twentieth-Century Cuba.

To learn more about the Afro-Cuban experience during the first half of the 20th century, I recommend Alejandro de la Fuente’s A Nation for All. In this book, De la Fuente presents the broad history of racism and discrimination against Black people and their struggles for equality before the 1959 Cuban Revolution.

The revolution led by Fidel Castro after 1959 intended to achieve more equality in Cuba. Although the long-term results were dubious and the changes were done by violating individual freedoms, it is the case that across many indicators, those at the bottom of the society benefitted for a while under Castro’s state-led equalization.

A well-researched book on the degree of success of the revolution in achieving racial equality is Devyn S. Benson’s Antiracism in Cuba: The Unfinished Revolution. The author argues that ideas, stereotypes, and discriminatory practices dating back to colonial times persisted in Cuba despite significant efforts by the state to achieve social equality. Thus, those resilient racial structures are still present on the island.

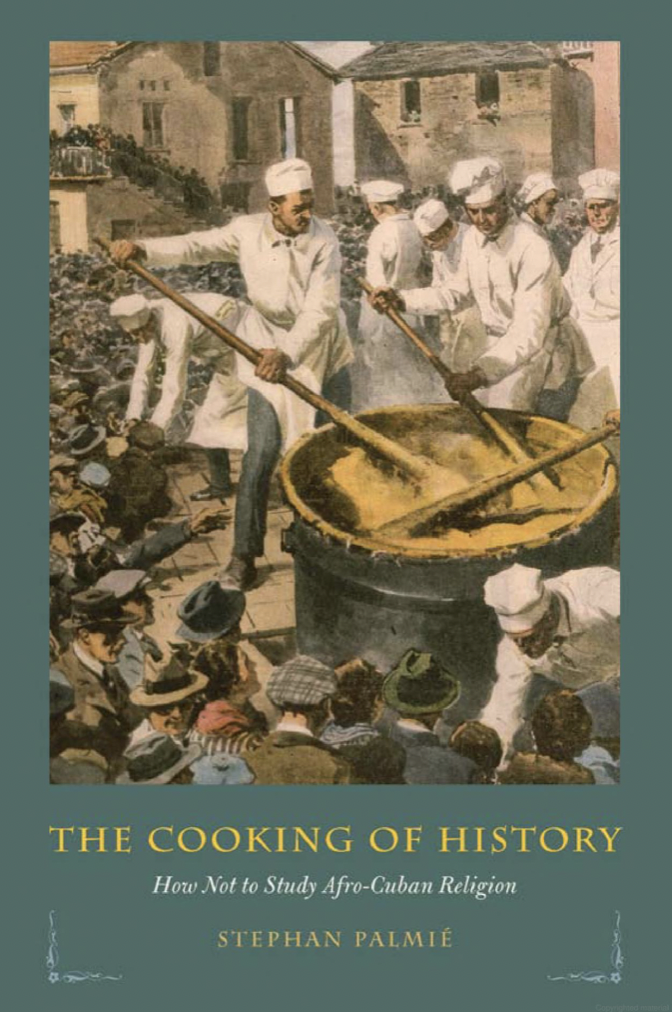

As mentioned at the beginning of this post, the cultural African legacy is an intrinsic part of what the anthropologist Fernando Ortiz called the Cubanidad or Cubaness. In Cuba and Its Music: From the First Drums to the Mambo, the American composer Ned Sublette presents a comprehensive picture of the African influence on Cuban rhythms. Regarding religion, over decades of studying Cuban Santería and Orisha worship Stephan Palmié published in 2013 The Cooking of History: How Not to Study Afro-Cuban Religion, a comprehensive study on the African religious influence in Cuba. The book is a historical account and a reflection on the methodology, often misleading, used by historians and anthropologists to understand the African elements in Cuba’s spiritual worldview.

There are some films depicting race relations and Afro-Cuban culture in today’s Cuba. The melodrama Honey for Ochun by Humberto Solás tells the story of a Miami college professor who travels to Cuba searching for his mother. Religion, love, and politics are intertwined in this film. An informative movie, in this case a documentary, is Henry L. Gates’ Cuba: The Next Revolution, in which the Harvard professor interviews scholars, musicians, artists, and regular citizens to understand the history of Blackness in Cuba.

Many historical events and transformations have linked the history of Cuba and the United States. One of them is the intertwined dyad of slavery and racism. Both countries experienced centuries-long exploitation of Africans as slaves, and racisms existed as the primary rationale to justify the system. Consequently, the struggle for equality links people of African descends from these neighboring nations. Black Americans and Cubans have often identified common ground in their struggle.

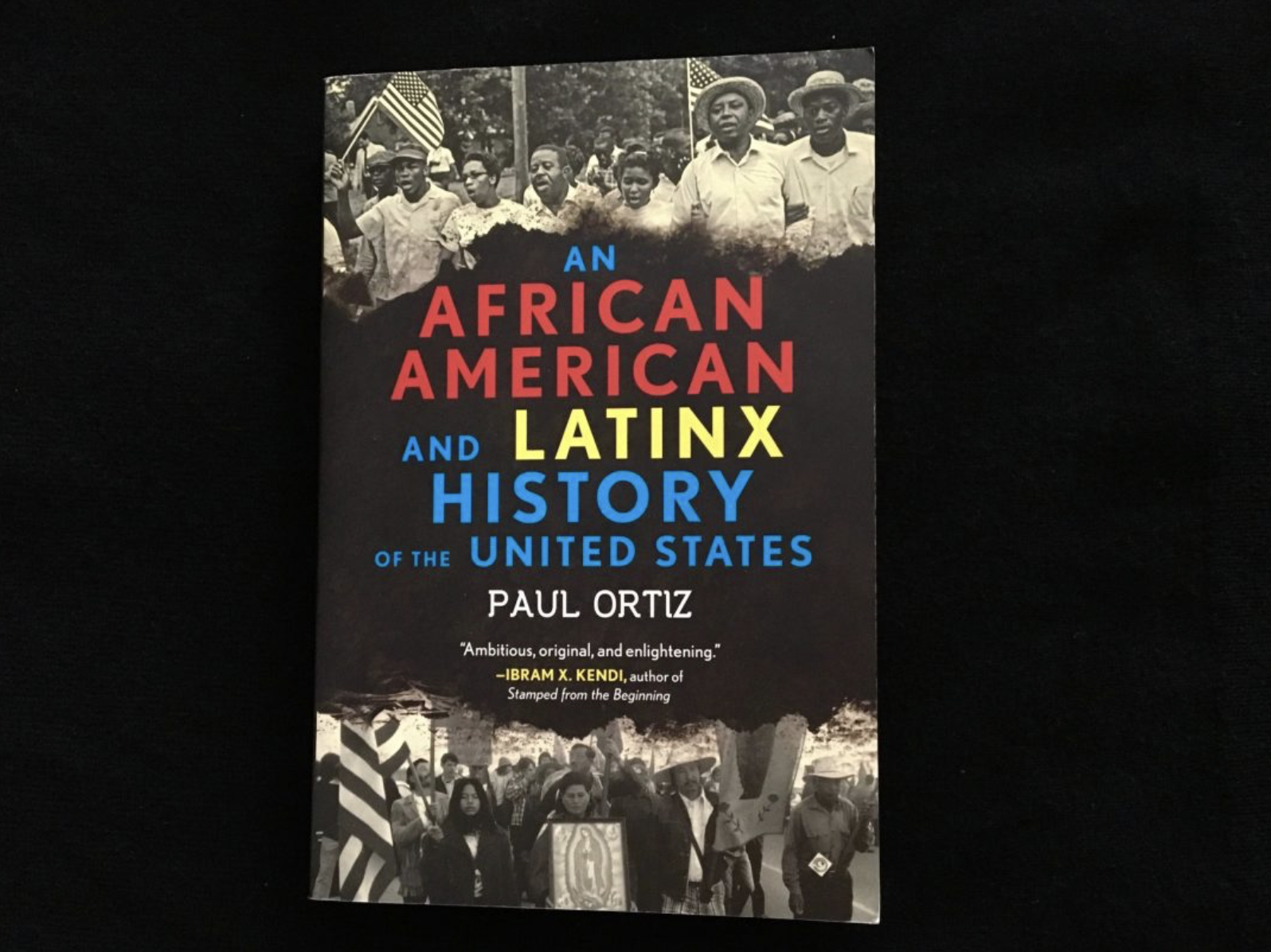

In the book, An African American and Latinx History of the United States, activist and historian Paul Ortiz explores the common cause for equality unifying Black Americans, Black Latinos, and other people of color. The fight for civil rights, Ortiz argues, goes beyond the American borders. It encompasses the global south. Ortiz traces this shared history back to the 19th century when Black and Spanish-language newspapers, abolitionists, and Latin American revolutionaries found a common cause against racism and imperialism.

In fact, Black abolitionists in the United States such as Henry Highland Garnet and Frederick Douglass paid close attention to Cuba’s own efforts to free itself from Spain through revolutionaries such as Cuba’s Black General Antonio Maceó. On the Cuban side, Ortiz notes that Jose Martí, considered the father of the first fight for Cuba’s freedom and a man believed to have had both Spanish and African ancestry, had written a eulogy to Garnet for the abolitionist’s passing. These liberationists understood that Cuba was especially vulnerable to that imperialism because of its close proximity, so the fight for emancipation of Black people in both lands was key to their survival.

Within each of the books, media, and films explored in this post, the readers can find more references to learn more about the experiences of Afro-Cubans, and hopefully, gain a better understanding of the community’s influence on today’s world.