Commentary: How I’m Using Education Programs for Migrant Farmworkers to Prepare for a Career in Teaching

I’ve picked all kinds of fruit and vegetables as a migrant farmworker child growing up between Florida and Michigan, and every state on the route between. But the one I most remember is apples. Starting at the age of 10, I’d wake up at 5 a..m. each weekend of Michigan’s cold fall days to help my parents pack meals and work tools into the truck, then I’d ride with them to the apple orchards. Upon arrival, it was my job to carry 12-foot ladders and heavy fruit-picking bags out to our work area while my dad drove a tractor full of apple crates. After that, I’d strap a fruit bag around my neck, tying its band around my chest, and I’d carry my ladder to the first tree of the day. On cold days, the frost-covered fruit would burn my small, bare fingers. Gloves wouldn’t help because they make the picking slippery, and hence, slower.

Within an hour, my body would go numb, forcing me to work faster in order to get the blood pumping. My neck and shoulder muscles got strained and sometimes even bruised from the weight of the apples I’d be loading in that bag. Hours of standing and climbing on ladders added to the pain. On good days, we’d leave at 6 p.m., but on busier days, we’d work past 9 p.m. By the time I’d get home, I’d be so exhausted I’d simply eat, shower, and go to bed, for the next day would be equally as brutal.

This labor was tough, but I take pride in having done it. Picking fruit taught me important life skills such as time management, quality control, and most importantly, the drive to finish high school and attend college so that I could enjoy a far more stable adult life, one with less physical risk and exhaustion, poor housing conditions, and constant relocation.

Keep up with the latest from UnidosUS

Sign up for the weekly UnidosUS Action Network newsletter delivered every Thursday.

The migrant education programs Redlands Christian Migrant Association (RCMA), an UnidosUS Affiliate, and the federally funded College Assistance Migrant Program (CAMP), gave me the tools and the foundation to do just that. For the past three falls, I wasn’t picking frost-covered fruit, but rather studying history and education at Michigan State University, where I’ll be a senior this year.

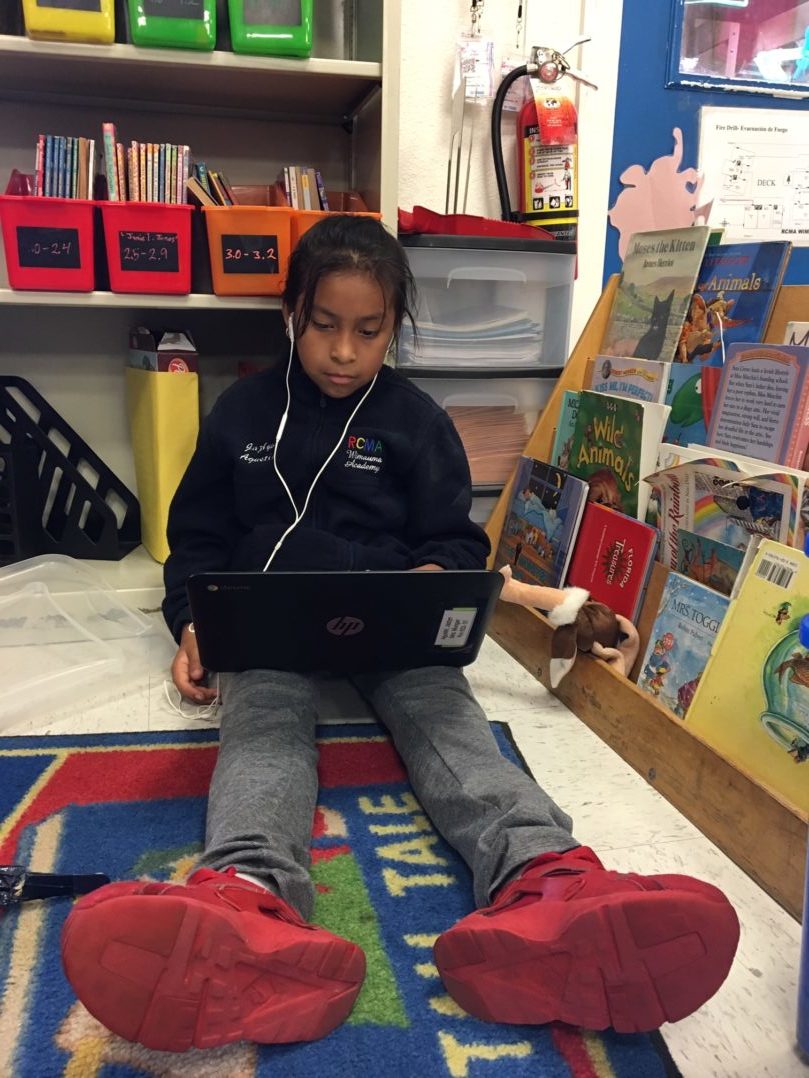

RCMA planted the seed in my pursuit of education by teaching me English for the first time. It also gave me a foundation in reading and math. Plus, my parents desperately needed child care and early educational support so that they could continue to work and know that I was safe and thriving. As I got older, the constant migration would cause me to miss a lot of class, and I rarely got any rest because I worked every weekend, summer, winter, and spring break. Still, the educational support I was given at that early age helped me to maintain my dream and finish high school.

The CAMP program would later help me in my transition to college. It started with the recruitment process. Representatives of Michigan State University’s CAMP program flew down to my small town in Mulberry, Florida to tell farmworker students like me about my options for exploring higher education. Not only were they quick to respond to my questions, they also met with my parents so that they too would understand how to apply for college and financial aid. They also invited my family and me to take a campus tour the next time we were in Michigan.

This was the first time my parents ever experienced something like this, and it was a very rich and proud moment for all of us. As a first-generation, low-income college student, I had very little knowledge of the expectations of college. I only knew it would be a struggle. CAMP helped by offering a two-week orientation before classes even started to expose me to all the resources available on campus. There were keynote speakers who came in to show support and share advice for success in college. I got to meet professors and counselors and ask them questions on what it takes to succeed in class. There were more informational meetings and classes on filling out financial aid, as well as financial coaching. And finally, I got the chance to meet the other migrant farmworker students in the program. Many of us quickly became friends.

But this was only the beginning of what CAMP has done for me as I’ve made my way through college. As a low-income student, there was no way I could cover all the costs of my studies and other expenses. CAMP took this barrier from me by providing a scholarship to pay for my tuition, housing, books, and meal plans.

This year, the Biden administration pledged $3 billion in funding increases for core federal early learning and care programs like Head Start, Early Head Start, and Migrant and Seasonal Head Start, as well as the Child Care and Development Block Grant (CCDBG) program. That money could serve up to 29,000 children in Migrant and Seasonal Head Start. The Biden administration has also pledged a a combined $66 million to help approximately 7,000 students in CAMP and the High School Equivalency Program (HEP), which provides migrant and seasonal farmworkers and members of their family the opportunity to finish their GED.

These funds allow more students like me to move forward with their American Dream. Through my work as an education policy and advocacy intern with UnidosUS, I am looking at how I can ensure that kind of support not only continues but increases. I am also gaining ideas for how I will take all my life experiences, my studies, and these supports into a career in education.

For most of my life, Michigan has marked my fall season, but Florida, the state in which I was born, marked my beginnings. Each spring, my family and I would wake at dawn and pack our truck for our workday in the fields, much like we did in Michigan. Because of the extreme heat and humidity, we always tried our best to arrive early. In Florida, my fingers never froze, but my back was always contorted. I would spend several hours bent over in the scorching subtropical sun picking strawberries and dropping them into my box. When that container was full, I’d struggle to stand up straight and walk to the truck to deposit the produce. If picking apples in cold fall weather in Michigan left me exhausted each evening, picking strawberries in Florida left me struggling to pull myself out of bed each morning. But I’m excited to continue in this circular geographic journey. Upon graduating in 2022, I hope to be back in Florida planting a new educational seed as a history teacher sharing the experiences of Latino farmworker families like mine with the next generation.

-Author Juan Vazquez is an education intern with UnidosUS.