Education Experts Offer Ideas for Accommodating an Influx of Afghan Refugees in Predominately Latino English Learner Classrooms

Growing up in Afghanistan in the 1990s, Sorayya Mohammadi yearned to be a teacher and often played a de facto one to her six younger homeschooled siblings. She was 16 when she and her siblings fled the staunchly conservative Taliban regime. That was in 2000, about a year before U.S. military forces invaded the country in retaliation for the 9/11 attacks, attributed to the late terrorist Osama bin Laden and his militant group Al-Qaeda, which was under Taliban protection.

“That was my dream—to be a real teacher in a real classroom,” says Mohammadi.

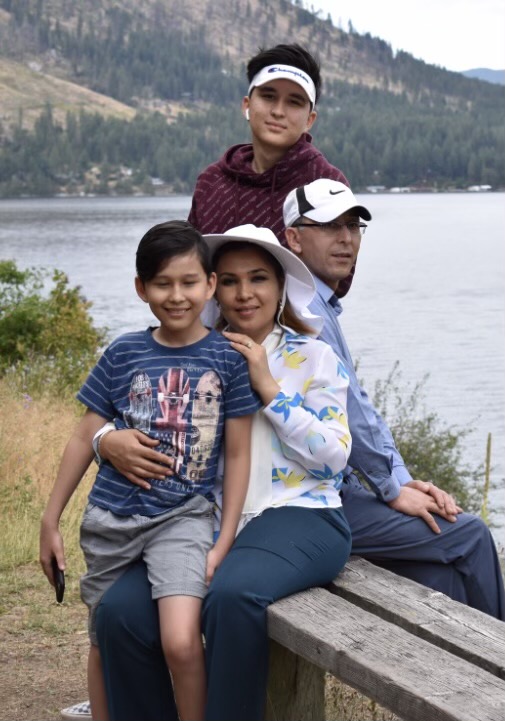

Obtaining a formal education would take decades. In Iran, the first country her family fled to, refugees weren’t afforded a right to a public education, so she bounced between outreach centers and some private schools. Then came a short stint in Turkey, where she was able to learn English and resettle in the United States with her husband and two children.

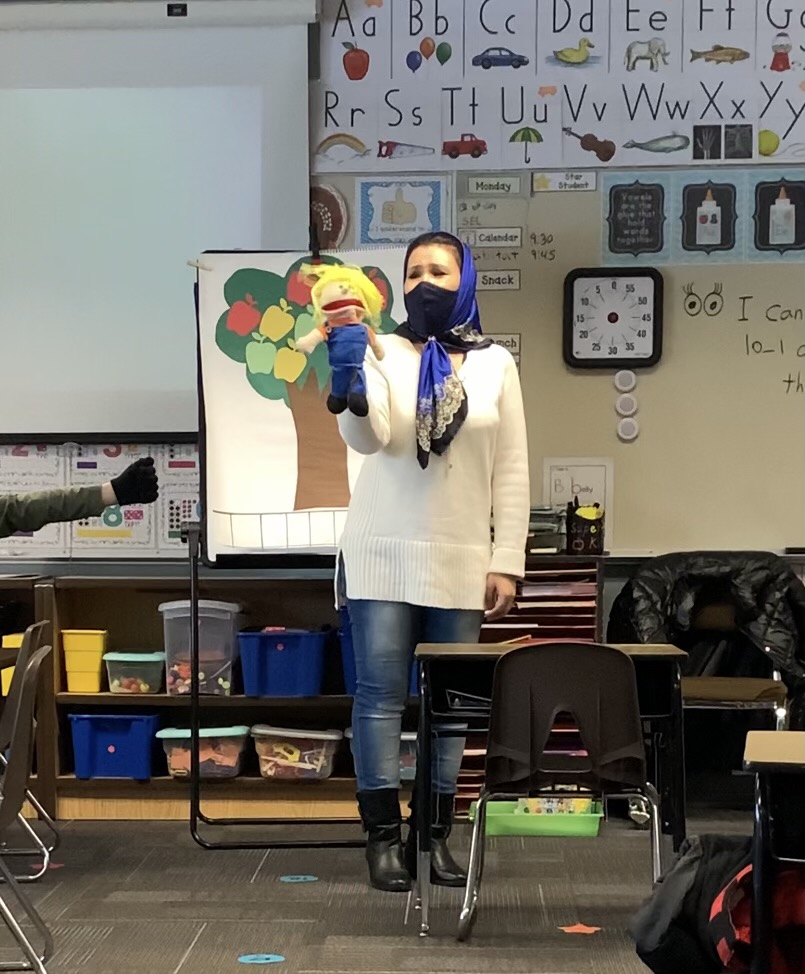

Today, she’s living her educational dream, exploring ways to honor all students their right to a high-quality education in the United States. In May, she completed her bachelor’s in teaching at Whitworth University in Spokane, Washington. This month, she’s building a warm and inclusive classroom of first graders a few miles away at Whitman Elementary, a predominately Black, Title I school with a growing number English learners (ELs). Most of the ELs are Latino, but some are from her native Afghanistan. She’s hopeful her experiences and insights will come in handy as many U.S. educators work to accommodate a new influx of Afghan refugee children.

Earlier this month, the Biden administration withdraw troops, a move that unexpectedly led to a fast return of the Taliban, sending many Afghans to apply for the United States’s refugee resettlement program. School systems in cities such as Phoenix, Dallas/Fort Worth, Las Vegas, and Chicago, will all need to prepare for a cultural and linguistic shift, especially since they are more accustomed to working with ELs from the Americas. While UnidosUS primarily serves U.S. Latino communities, it stands for civil rights, equal access to education for all students, and an understanding that while Latinos may account for some of the largest numbers of ELs in classrooms across the country, they aren’t the only ones. ProgressReport.co consulted with Mohammadi, the UnidosUS education team, and several other educational experts to come up with some ideas and best practices for accommodating this incoming group of Afghan students.

Start with a Warm Welcome

While it’s important that educators hone their knowledge of the history and origins of their students and ultimately create space for social studies around those experiences, Mohammadi says to start with more symbolic activities.

The one Afghan student in her first-grade classroom is lucky enough to speak her native Dari, one of two main Afghan languages, but right now, he’s really shy.

“Sometimes when I see he’s very quiet, I start talking to him in his language to comfort him,” she says.

But with or without a common language, she knows from her own refugee experience that it takes time to feel safe in a new environment and to get to know those around you. As such, her first classroom activity was to take a photo of each of her students, have them cut colored paper into flowers, and use their headshot as the center of each flower. Then she put all the flowers in a pot and asked them to think about why it was so important to include different colors and styles of flowers.

“How can we use our differences to grow?” Mohammadi asked them. “We talked about why being different is good and valuable,” she added.

The next exercise was to talk about their favorite things, such as colors, foods, and activities. Even with limited English, her Afghan student can start to envision what they’re discussing and get inspired. Next week she’ll instruct her students to go home and ask their parents about the origins and meanings of their own names.

These activities, she says, are the “basics that allow us to consider how we all share common experiences and bring ourselves together.”

Veteran anthologist and child and immigrant advocate Carolyn Rose-Avila concurs. In a 2019 blog titled “Help and Hope: Here Are Eight Ideas for Supporting Children Coming Out of Migrant Detention Centers,” she told ProgressReport.co that talking about flags of each student’s country of origin can also be a good icebreaker, one that allows them to take pride in the unique customs and lifeways of their people. This creates a door to the world in which educators and community organizers can then provide COVID-safe trips to local museums or engage students in virtual visits.

“Yes, they’re in a tough situation, you want to have time to hear what their fears and concerns are, but you don’t want to make this a horrible tragedy all the time,” she noted.

But even as this sharing of basic human experiences is important, traumatized children should be given physical or virtual space when they need to withdraw or check out, says Rose-Avila.

Now a migrant and refugee community organizer based in Atlanta, she drew from her work as the former director of Save the Children Latin America and the Caribbean in the 1990s and as the former Haiti director for World Vision in the mid-2000s.

“When you have this kind of a crisis, everyone is stressed out, the parents are stressed out, there’s no home, no water—you don’t want the children to have to constantly hear about this horrible situation, so I love the concept of the child-friendly space,” she told ProgressReport.co.

She suggested creating safe, fun corners within community centers, classrooms, or at home where children can spend some time distracting themselves from these stressors. This space could include colorful artwork, fun photos, stuffed animals, toys, games, or materials to make art projects.

Holding Space for Deeper Discussion

Sooner or later, tough, uncomfortable, and insensitive questions are bound to arise, notesUnidosUS Director of Parent Engagement Jose Rodriguez, who taught many refugee students, including Afghan children in schools in Texas.

“If they had names like Mohammed, sometimes other kids would ask ‘are you a terrorist?’” he recalls.

If a student was from a country like Rwanda or Burundi, classmates might ask about genocide, or one from Central America might be asked about gang violence. Now, with the return of the Taliban to Afghanistan, students are sure to ask questions about Muslim extremism, gender discrimination, and maybe even U.S. foreign policy.

“Kids are very curious, and they’re all feeling a bit traumatized by what they hear on the news,” Rodriguez explains.

By creating a classroom that is welcoming and safe, educators can turn these awkward if not offensive questions around. Rodriguez says school administrators, teachers, and parents should reach into their communities for geographical, cultural, and linguistic assistance.

“I was lucky that here in San Antonio because it’s a military city, so I had access to military language schools. I also reached out to local universities, especially ESL departments,” he adds, noting that these institutions may have access to academics who speak the languages of these incoming students, and who can also interpret cultural norms. They can even be invited to give a presentation.

And with this new Afghan refugee population arriving, many educational organizations are putting together Afghan-specific resources pages. One of the most popular comes from Colorín Colorado, a site for educators and families of ELs sponsored by PBS Television and the Teachers Federation of America. It has created a page titled “How Schools Can Partner with Afghan Refugees and Families.”

The page provides schools with what they need to know, lists all major cities resettling Afghan refugee families, offers recent articles and interviews about lessons learned from accommodating these families in the past, as well as updates and explainers, classroom resources, and ideas for how to help and partner with these students and families. This includes everything from strength-based approaches to teaching ELs to supporting the social and emotional health of newcomer immigrants.

Alejandra Domenzain, a former UnidosUS education specialist who now works as a worker rights advocate and recently published a children’s immigration story titled For All/Para Todos, suggested several resources to get classes thinking more generally about migration issues.

She suggested the following resources for general awareness of migration issues:

- The Anti-Defamation League’s Immigration Page can offer educators fact sheets about refugees and immigrants, as well as current U.S. policies related to them.

- The nonprofit organization Re-Imagining Migration provides toolkits to educate youth to “respect, work, and live with differences,” and to see that effort as “essential to the future of democracy.”

- The websites I’m Your Neighbor and Read Brightly offer a wide array of children’s books and activities ideas for welcoming new migrants and refugees.

- Colorín Colorado provides a book list with a wide array of books about cultural diversity and social inclusion.

- The website Social Justice Books helps students take a deeper dive into discussions of immigrant rights.

“Not only are immigrants making contributions to our economy by their labor and contributions to things like Social Security and taxes, but they are also actually the ones that are pushing us, inviting us, forcing us to live up to that promise of justice for all,” Domenzain told ProgressReport for a recent blog about teaching migration issues.

Supports for ELs

For more than 50 years, UnidosUS has always known that providing supports for ELs is one of the ways to help students who are migrants, refugees, or children of foreign parents become those agents of change. In fact, UnidosUS’s education team often reflects on how Latinos came alongside a group of Chinese parents who won the 1974 Supreme Court case Lau vs. Nichols to do just that.

“Welcoming K-12 ELs into the schools, properly assessing their language proficiency, and placing them in the appropriate ESOL/ESL program is key to the success of the whole student population and the future of our country,” says Rodriguez.

Still, schools often struggle to quickly meet the demands of students speaking languages for which they don’t have immediate resources. Rodriguez found that some of his Afghan students gave him a quick solution. They would write down every English word they didn’t know in their notebooks, find the equivalent in their native language, and then write the English word out again three times.

I asked them to share these notebooks with me so that I could copy them for other students,” he says. He would also order dictionaries in Dari and Pashto with the corresponding English words.

“They were very appreciative, and it helped all the ESL students in the classroom to embrace each other because the one thing that they have in common is that they’re learning English and they’re working together,” he adds.

As bonds between students form, so too should those of their parents, something he stresses in the UnidosUS parent engagement program Padres Comprometidos.

“Language and cultural differences keep many parents from becoming involved with their children’s school as does, for some of them, their economic background,” says Rodriguez. “Other parents may have themselves failed in school and the inadequacy they feel is what keeps them away. Some parents may have had negative experiences with the school system. Others may feel the school has a negative perception of them, so they do not feel welcome. And others simply don’t know exactly what to do to become involved in their children’s school or their children’s education.”

In Padres Comprometidos, he says, families are encouraged to use their native language at school and at home as they are learning English. If children are doing remote learning, the schools need to provide ongoing support and language accommodations, something that can be enhanced by providing those dictionaries and fomenting ties to community leaders and experts with strong linguistic and cultural ties.

“From my own experience as an ESL (English as a Second Language) Coordinator I have seen the Latinx community embrace other ESOL students into their communities because they share one common goal and that is that they are immigrants and are all learning together to ensure that their children are happy and successful,” says Rodriguez.

These are things Mohammadi laments she never experienced as an Afghan student refugee in Iran, where the main language is Farsi.

“I never felt welcomed or like I belonged there,” she notes. “Now as a teacher, I let my students know that no matter what language they speak or where they come from, they are all welcome, they all belong in the classroom, and we are all one big family. It brings down their stress levels and make them ready to learn.”

Author Julienne Gage is the editor of ProgressReport.co.