How parents and educators can use children’s books as a ‘magnifying glass’ for injustice

Books for children can serve an essential role in helping kids learn how to think, process, and analyze what they see, including issues like racism, immigration, and economic struggle. Recent calls for more diverse children’s books promote the idea of using books as “mirrors” to see yourself reflected, “windows” to witness another’s experience, and “sliding glass doors” to enter into imagined worlds. To extend the metaphor, what if we also saw books as a magnifying glass through which young people can learn how to look more closely and “read” the world more deeply? Parents, educators, and other adults in children’s lives can model how to use books to examine the social, political, and economic causes and consequences of what’s depicted in a story, and explore how those stories can reveal broader realities.

For example, when characters are facing economic hardship, we can show kids how to understand why the characters may be in that situation. Are they working for poverty wages? What might happen if they ask for better working conditions or leave that job? Are there racial, gendered, or other patterns to who has access to economic advancement? What policies and systems perpetuate poverty?

Likewise, when reading stories of challenges faced by immigrants and refugees, we can encourage children to explore those situations further. What are the dynamics forcing people to migrate, including those created by our own political and economic policies? Did these characters have any option to migrate with a different status? Are there racial, geographic, or other patterns to who migrates and why? How has citizenship been defined historically, and how have immigrants of different races been treated?

In each instance, we should encourage kids to consider three central questions: Who benefits? How can these systems and policies be changed? What is already being done to make things more just?

Some books are designed with on-ramps for those discussions. Others require more on our part to make the connections. There are a growing number of organizations curating book lists and developing lesson plans to support educators and families ready to engage.

For those who want to select books and design lesson plans or conversations that plant the seeds of curiosity to think more about race, gender, class, immigration status, and more, here are some questions for educators and parents ask:

- Do you have books or lesson plans that identify and question the systems, institutions, laws, and policies at the root of the problem? Do they provide clues or answers about who benefits and who is harmed?

- Do they point to or address issues of power—who has it, who doesn’t, and why?

- Do they show how systems, institutions, laws, and policies can be changed?

- Do they show diverse characters as agents of change, including those that are impacted as the leaders?

- Do they show movements and collective action of ordinary people, or only single out individuals as heroes taking actions that can’t be easily replicated?

- Do they portray social problems and changes needed today, and not just what was done in the past?

- Do they represent current movements and struggles for justice that students can support or join?

Most of us have not been trained to ask these questions or to guide children through this process, unless we’ve had the rare opportunity to be part of a community that wants to equip young people with these tools. And now, many politicians are actively discouraging these conversations by trying to prohibit teachers from addressing systemic racism (framed as an attack on “critical race theory”).

Some see it as essential to preparing young people to understand their society and play an active role in making things better. Others feel threatened by it. Teachers know that books are some of the most effective tools to help children better understand the world, and this is essential to ensure the next generation is fully informed and civically engaged. Here are some of the arguments against teaching the truth and how to respond.

“Kids are not ready to confront social issues.” Children are already impacted by or witnessing these issues and are processing what they mean. The issue is whether we give them the space and support to do so or whether we leave them to cope alone. Even those children who you think have not been exposed to such issues are ready to talk about them. From the time they can speak, children ask “Why?” and are quick to point out “That’s not fair.” Kids are wired to wonder, instinctively rebel against unfairness, and have an untainted impulse to do the right thing, given a real choice.

“There’s only so much you can do with a children’s book; it’s not a textbook.” Almost any book can be a starting point to think critically. If a social issue is even hinted at, you can go beyond the surface level problems to probe the root causes, which are usually historical and structural. If the book is less enlightened and more problematic, you can model how to think about points of view that aren’t represented in the story, how to consider limitations of the author’s perspective, and how to spot inherent assumptions that can be questioned. Almost any story you read can be placed in a larger context that gives insight into social, political, and economic dynamics.

“We should wait until kids do their ‘civics unit’ in high school to get into policy issues.” Nationally, there are no uniform programs to teach civics, and there are fundamentally different visions about their purpose. Some believe that these programs should glorify American institutions and history while inculcating the importance of the rule of law, while others believe that civics should teach us to question flawed systems and give young people hands-on experience with making the case for changes they want to see. It can be powerful to start this process in elementary school so that kids will incorporate a structural analysis into their day-to-day thinking, rather than depending on a teacher to introduce this skill later on (if they are fortunate). As a reality check, more than half of adults can’t name the three branches of government, so the more we can do to start kids thinking about how policies are made, the better.

“It will make some families uncomfortable.” Millions are already uncomfortable with the status quo. In fact, much more than that: the lives of Black, Indigenous, and other people of color, disabled people, low-wage workers, housing insecure people, LGBTQ+ people, immigrants, and other marginalized groups are negatively impacted by these unexamined systems. One group’s comfort can’t be at the expense of another’s basic rights. We can’t avoid discomfort; we can use it as a guide to identify what is not working for everyone. Further, we have the opportunity to redefine what topics should be part of the public discourse, invite young people to develop an informed and principled position, and model how to engage in productive and nuanced debates. What seems uncomfortable to us now may become less so as we build our capacity to address difficult issues and allow ourselves to be motivated by a commitment to the common good.

“It feels unpatriotic to be critical.” We live in a culture where we’re encouraged to believe that it’s unpatriotic to question things that we now see as deeply misguided or even immoral. We have a moral obligation to examine our history, institutions, beliefs, and systems to see if they are defensible, and if not, to correct them. If we value the lofty ideals we claim as the defining principles of our country (even if they have always been aspirational), what is more patriotic than figuring out what needs to be done to fully realize them?

“This critical approach will lead to young people wanting to change things.” It’s true that looking closer and learning new things can often change our views and cause us to take different actions. But if we want to nurture new generations that participate actively in democracy, decision-making, and community engagement, do we actually want them to do it from a place of limited knowledge and analysis? We have to trust that shining a light on the dark places will give the next wave of leaders greater awareness of where they might be ignorant and willingness to be corrected and do better. For me, this is the most exciting part. I picture young adults who have been taught to see the world through the lens of justice from the very beginning: What truths and contradictions will they be able to hold that we take for granted? What better systems might they imagine and build? And what will they do to ensure that they pass on that same clarity, courage, capacity, and awareness to those that come behind them?

This is a good time to affirm that we don’t need to protect children from complex realities; instead, we need to arm them with awareness and analytical tools. As a former teacher, I know there are developmentally appropriate ways to do this at every age. As an author, I hope to contribute more resources for families, teachers, and librarians to teach young people to question and think critically about what changes they want to see. As a parent, I am grateful for the books that help me have those conversations. Let’s recognize children are capable of engaging in important topics with good books and appropriate support. Let’s value their role as future civic actors. Let’s write, read, celebrate, and demand children’s books that are mirrors, windows, glass doors, and magnifying glasses.

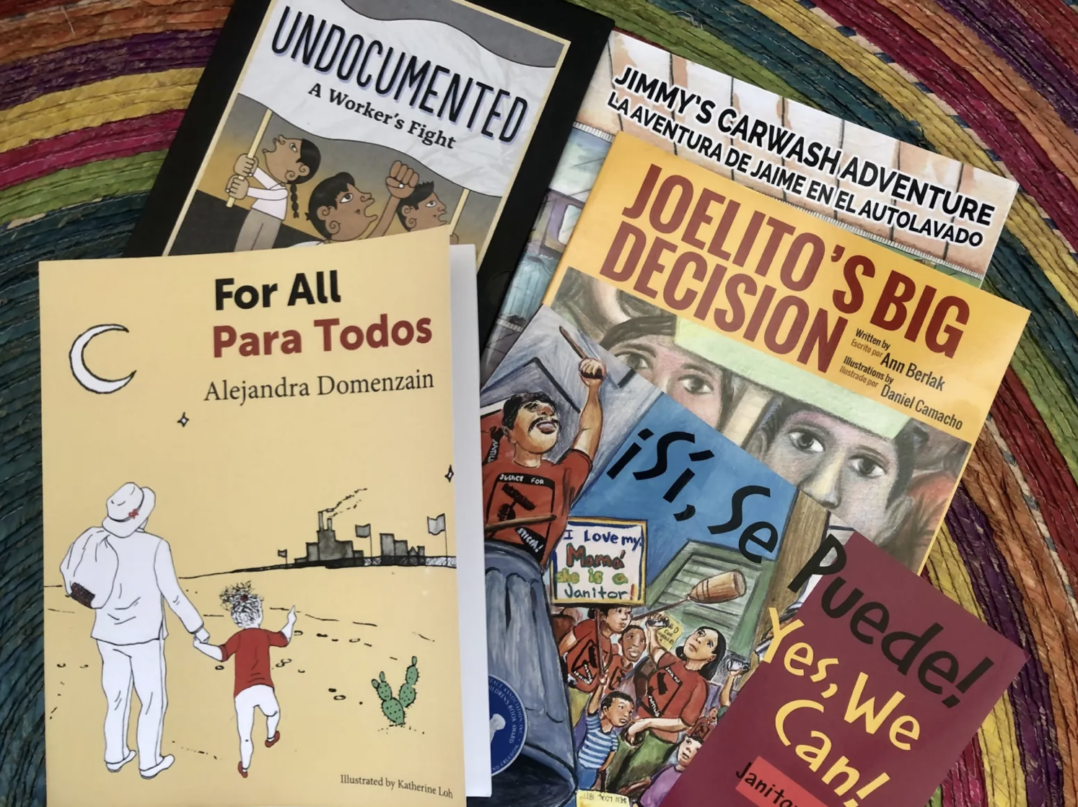

-This article is first published in Prism Magazine on September 8, 2021. Its author, Alejandra Domenzain, has been an immigrant worker rights advocate for 20 years, was an elementary school teacher, and is the author of the bilingual children’s book For All/ Para Todos. She is the daughter of Mexican immigrants and lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.