Q&A: City of Tucson Climate and Sustainability Advisor Fatima Luna Shares How Her Studies and Experiences Improve the Environment

Growing up in the tiny, mountainous community of Mezquital del Oro in Zacatecas, Mexico, Fatima Luna always saw her community as beneficiaries and stewards of the ecosystem. Upon emigrating to Orange County, California as a teenager in the early 2000s, she found community, but not necessarily environmental awareness. It prompted her to study environmental issues and public policy at the University of California Berkeley, and today, she’s forging a space in a traditionally white, male-dominated environmental movement as the climate and sustainability advisor to Regina Romero, Tucson’s first female mayor.

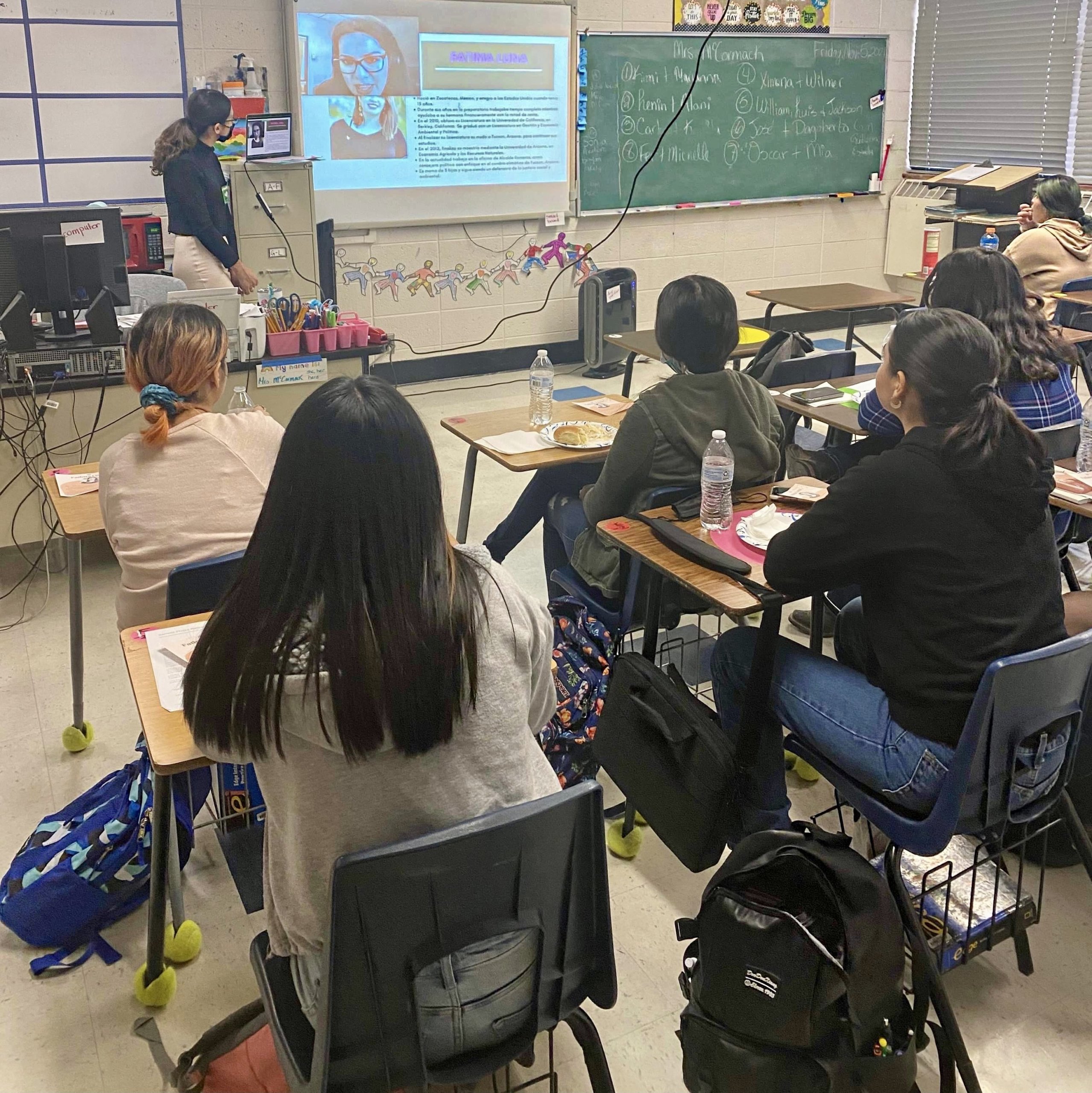

Last year, Luna spoke via Zoom about her work with participants of the UnidosUS Affiliate Amistades Inc. chapter of Entre Mujeres, a program founded in 2016 with the support of UPS to address the pressing needs impacting the lives of Latinas. Following the event, the Entre Mujeres students created informational flyers to promote this work with family and friends. And this month, ProgressReport.co caught up with Luna to help other Latinx students consider how their studies and civic engagement could promote sustainability and stewardship in underserved communities.

Q. How did growing up in Mezquital del Oro instilled your sense of oneness with nature?

Keep up with the latest from UnidosUS

Sign up for the weekly UnidosUS Action Network newsletter delivered every Thursday.

A. The town is so beautiful and biodiverse that it could pretty much be a natural reserve, so I grew up practicing sustainability even though we didn’t call it that. We didn’t have much, so we dried our clothes outside, and we recycled everything from clothes to furniture. There is no irrigated agriculture, so farming was based on the rainy season and we ate accordingly. We also built basins in the trees to capture storm and rainwater, something that has been embraced in urban planning as a green infrastructure practice. We walked and biked almost everywhere. When I moved to Orange County, I realized the beauty of simplicity that I had in Mexico foundand found that I had a desire to help preserve ecosystems for future generations.

Q. What cultural, logistical, and environmental challenges did you face upon emigrating?

A. I migrated alone when I was 15 because I had an older sister who was to take me in. I had to learn the language, and a whole new way of life. It really shocked me that there was this attitude of abundance about everything, like wasting food. Growing up, whatever food we didn’t eat we fed to the animals or composted it. Still, I had no choice but to build community around me. I forged that with my high school teachers and by working at a small Mexican restaurant.

One teacher, Mr. Jimenez, understood the struggle of students like me, and he went out of his way to help us navigate the system. He would convene us to the school on Saturday mornings to study English and math for our high school exit exams. My parents made a huge sacrifice in sending their youngest of five children to the United States, so I did my best to study and to seek out people who could guide me through the process of applying for college and scholarships. I was able to start at community college and then transfer to University of California Berkeley for a major in environmental economics and policy.

Q. What classes did you take at UC Berkeley?

A. I took classes in environmental science, environmental policy, economics, and statistics but I also took courses in Chicano and women’s studies. That intersection provided the quantitative and qualitative tools I needed to play a role in this field. A lot of the articles that I was reading mostly used numbers to make a case for environmental concerns. The Chicano and women’s studies classes I took gave me a more complete picture than what we were seeing with the usual environmental rhetoric—untold stories.

Q. What are some of those untold or now-emerging stories?

A. Studies show that race and not so much class is the most likely significant correlating factor for the placement of toxic facilities. For example, in the United States, Black, Indigenous, and Latinx, communities are more likely to live within two to five miles of industrial sites, landfills, and congested highways. Low-income communities of color are also less likely to have much tree cover. These environmental concerns contribute to polluted water, poor air quality, and rising temperatures, and they can negatively affect the health of a community. That’s why you have higher rates of ailments like asthma, obesity, decreased fertility, and cancer in populations of color. All of this is the result of environmental injustice and historic racist practices such as red lining real estate. Last year, a study by MDPI, a Swiss organization focused on open scientific exchange, found that neighborhoods that were previously redlined are now five to 12 degrees hotter in the summer. These neighborhoods are more vulnerable to heat, which can be detrimental for peoples’ health and safety, but also drives up the cost of electricity for the families living there..

Q. How are you seeking to address these types of concerns in your role as climate and sustainability advisor for the City of Tucson?

A. One major project I’m working on is Mayor Romero’s Tucson Million Trees initiative in which she hopes to plant one million trees by 2030, with an emphasis on planting them in communities of color. We’ve essentially replicated the American Forest Methodology’s tree equity score in which we map neighborhoods and come up with a composite score to evaluate the need and priority for trees to improve neighborhood’s overall tree cover. In addition to lowering the cost of energy, these trees provide habitat for different wildlife, including birds.Trees also improve air and water quality, improve walkability, and cool neighborhoods. Extreme heat is a very real climate threat in our desert community and planting trees is an easy and relatively affordable way to increase resilience.

Q. How is the program implemented?

A. We partner with the local nonprofit Trees for Tucson and, with financial support from corporations such as Mister Car Wash and Tucson Electric Power, we work with neighborhood leaders to make sure that we design tree planting and green infrastructure projects that can easily be adopted by the community. For example, we’re pairing Tucson Million Trees with another City of Tucson initiative known as the Green Stormwater Infrastructure project in which we divert storm water from the streets into basins to capture and retain stormwater that can water the trees and other vegetation. This is important to a hot, desert terrain because it replenishes the aquifer while watering the trees and improving the ecosystem’s biodiversity.

Q. What kinds of trees are you using for the One Million Trees Initiative?

A. We focus on desert and shade trees that will survive on less water. We prioritize native trees such as the desert willow, palo verde and the mesquite, which is actually the tree for which my own village in Mexico was named after. Families can sign up to receive up to three trees per household and our partners at Trees for Tucson will work with them on the weekends to plant them.

This is one of the areas where we encourage students to get involved. Working with our partners, we train youth to canvas their neighborhoods, raising awareness about the benefits of the program. The youth receive a stipend for their work as well as training on how to plant and tend to the trees with the goal of eventually teaching them to harvest seeds and grow them in a nursery. It’s a great use of human capital and they get all these skills that can potentially turn them into urban foresters.

Q. What advice do you have for Latinx students who want to follow in the footsteps of someone like yourself?

A. At the high school level, I would say pay attention to those civics and history classes. This is where Latino, Chicano, and ethnic studies come into play. Then I would say volunteer with local environmental campaigns or groups doing environmental or climate-related work. Get to know elected officials and attend city council meetings to learn about the policymaking process. You can also identify some areas of interest like, water or energy, then read the news and find mentors who can talk about career paths. This can set you up for picking an area of study in college.

But I also want to tell students to really embrace who you are and where you come from. Oftentimes we Latinos undermine our lived experiences and the power and the knowledge that we carry through our lineage. You know the stereotypes—that Latinos don’t go hiking and they don’t care about certain issues, but that’s a dominate narrative created by the dominate culture. We have to disrupt that narrative. I grew up hiking and recycling. Our relatives have often practiced sustainability, so talk to your elders.

It can be uncomfortable at first. I was initially shy when attending conferences in these old, male, white dominant spaces . I did not grow up with all the jargon, but then I realized that I need to embrace where I come from. We belong in those spaces and we enrich them. Without voices like ours, we can’t change the narrative.