UnidosUS’s Education Programmer Jose Rodriguez Started School During the Civil Rights Movement. Five Decades Later, He’s Still Advocating for Change.

The educational life of Jose Rodriguez, a senior member of UnidosUS education program department, has been tied up in the civil rights movement for as long as he can remember. In 1963, he walked into kindergarten and did what children his age usually do—he started asking questions. But instead of getting praise for his curiosity, he got a spanking. The reason? He wasn’t supposed to be speaking Spanish.

More than 50 years later, that moment still stings, but civil rights legislation and countless local advocates like Jose have changed our education system by demanding equal opportunities and fair treatment for all children. As Director of Parent and Community Engagement at UnidosUS he’s made it his lifelong vocation to work toward more humane and egalitarian educational practices that meet students where they are, in whatever language they speak.

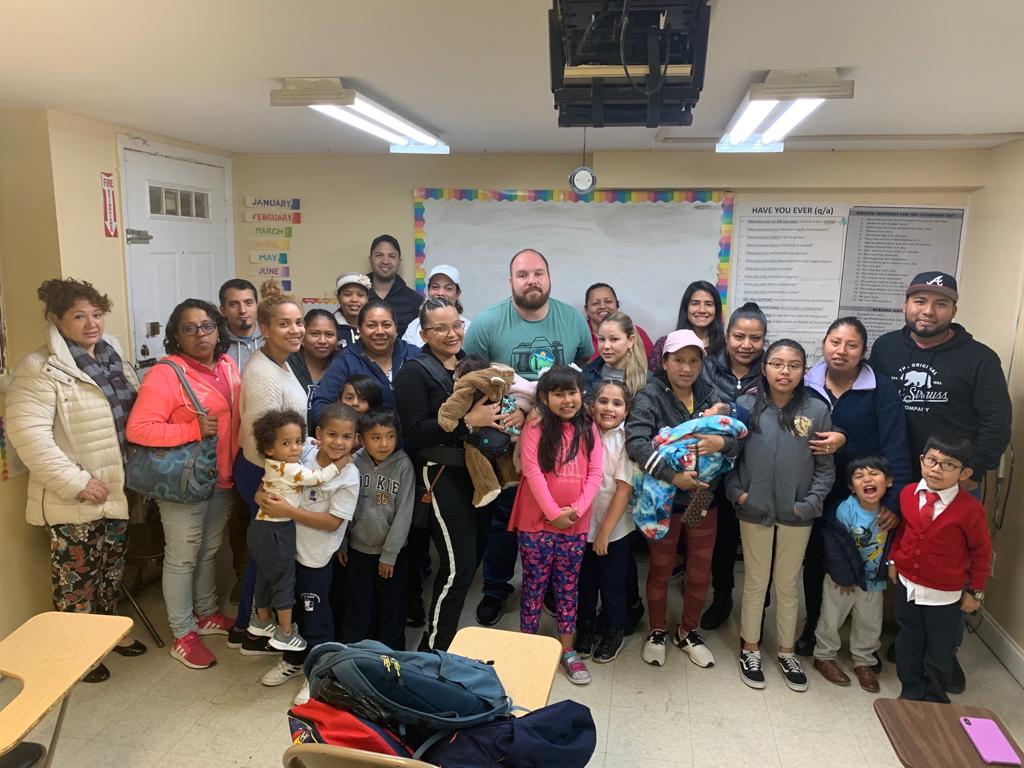

Jose’s time in public schools as a student, teacher, administrator, and family engagement specialist, are a case study in how civil rights law can change our schools – and he sometimes uses that story to teach families how to advocate for their children through Padres Comprometidos, a parent engagement program he runs at UnidosUS.

Keep up with the latest from UnidosUS

Sign up for the weekly UnidosUS Action Network newsletter delivered every Thursday.

“I do this activity with the parents called Looking Back and Looking Forward. I tell them: ‘think about when you were 12 years old. Write those things down,’” he says. “And then I say, ‘okay, how is the education system now for your children? What will remain the same and what will have changed?’”

The goal is for parents to learn about their rights within the school system, including laws that protect students and families and how they impact both students and their teachers. Jose’s story shows how these rights have advanced over time, and highlights the need to protect and defend them from current attacks.

The 1960s: Equal Access to Education

Jose’s story was not unusual for his generation, but it highlights the need for civil rights legislation, and the progress or challenges its faced since its inception.

“I grew up in a rural community in the Rio Grande Valley of Texas, and I started school in 1963. My parents are both fifth-generation Texan, so my parents went to school until about the fifth, sixth-grade level. They could read and write in English and Spanish, and they could speak it as well, but the home language was Spanish,” Rodriguez says.

The day of the kindergarten spanking, Rodriguez asked his classmates why he was punished, and was horrified to discover that they too scolded him for speaking Spanish. The trauma of the incident was so severe that Rodriguez quit speaking for nearly two years. He did, however, continue listening, and as a result he learned to read and write in English, and to be conversational when he was ready. But by then, he was placed in a track of courses for “low-achieving” students.

The education Jose received was unequal, and the school did not provide him with resources to learn along with the other students. “There was no legislation. It was just sink or swim,” he recalls.

Two years later, Congress approved the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965. Title I of that law established equal access to education, including high academic standards and accountability, and dedicated federal money to help schools serving low-income students (Title I funds). Equal access, standards and accountability have all evolved over time, as the law has been reauthorized and even changed its name. But the goal of the law remains: to make sure students like Jose, or any other child arriving in kindergarten are treated fairly and had an opportunity to learn.

In 1968, the ESEA was amended to include Title VII the Bilingual Education Act, which provided funding for English learner programs, including the establishment of EL support centers. By then, Rodriguez had already gone through almost his entire elementary program without such supports, stuck in a tracked system and labeled a “low achiever.”

“While in school, I was not aware of the education laws that were in place, however the school began to implement programs we didn’t have before, for example, remedial reading classes and remedial math classes. Through Title I of ESEA we had access to state-of-the-art reading laboratories where our reading level was assessed,” recalls Rodriguez.

The 1970’s: Rights for English Learners and Students with Disabilities

Even after ESEA, students were routinely punished or shamed for speaking a home language. In 1974, the Supreme Court case Lau v. Nichols ruled that public schools must provide a meaningful education to non-English speakers based on the civil rights act of 1965. This began the process of securing quality education for English learners and dual language learners.

By middle school, the tracking system was less rigid, but students learning English had to cope without additional support. Then in 1970, the US Department of Education sent out a memorandum stating that districts could not exclude children from effective participation in their educational program because they did not speak English. The districts were required to help students learn English, give them true access to the same educational opportunities as other students, and include families who did not speak English in their communication. There was particular concern about segregation by tracking and ability.

But clearly not everyone got the memo. One day Rodriguez says a group of students from his small-town school were selected to visit a college campus and he wasn’t on that list.

“My mother called the school principal and asked that they take me on that trip because I was going to go to college. It is because of that visit that I was inspired to do better in school,” Rodriguez says.

His mom’s effort paid off. He went on the campus visit, and then went on to study at the same university—Texas A&M.

Rodriguez graduated high school in 1975, just as another landmark piece of legislation took effect. Now referred to as the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act ensured that all children with disabilities, including those who were blind, deaf, emotionally disturbed, or had down syndrome, could attend public school with everyone else.

English learner status is not a disability, but the tracking at Jose’s school was another example of differential treatment that harms English learners and students with disabilities. All of this got Rodriguez curious about the emerging field of bilingual education, and Texas A&M was one of the first schools in the country to offer this major. Rodriguez found that he performed well in all subject matter except English. He spoke and read the language all the time, but he struggled with grammar and with writing composition. As he moved through advanced Spanish, he noticed how reading and writing in his first language improved his English skills as well. Research has shown that reading and writing skills in students’ home languages are crucial supports to learning a second language, and through the Padres Comprometidos program Jose teaches families this important message: read and speak and write to your children in whatever language you prefer, just read to them.

Education Theory vs Practice

After graduating with an education degree in 1980, he started teaching Spanish at a middle school in Crystal City, Texas. He quickly discovered that many students were unable to read in English or Spanish, and that recent immigrants weren’t getting proper language support.

Other people tried to tell him those parents didn’t care about school, and the kids didn’t either, “ I just didn’t understand that, so I started doing home visits and getting to know the community,” he recalls. What he usually found was that parents had high aspirations for their children, and that those children truly wanted to learn, but it was hard to stay motivated without proper support.

“One student told me ‘the reason we act bad is because nobody cares about us. We have new teachers every year. No one stays, so why should we care?’” recalls Rodriguez.

Like so many teachers, Rodriguez became frustrated with this dismal state of affairs and he accepted a new job teaching Spanish and drama to elementary students at a private school. Located in a more affluent part of the city with a much wider array of resources, Rodriguez was able to see a different kind of education.

“That was where I needed to be,” he says, noting that he learned all about best practices for teaching literacy, and he was able to see how parents who felt empowered were engaging their school system.

“Every day parents came up to me and asked about their child’s progress, and how they would help their children at home,” he says.

After six years in that environment, and obtaining an elementary education certificate, he accepted a position teaching theater arts at a low-income school in the Edgewood Independent School District. There he was shocked to discover that many elementary school students couldn’t read basic scripts for plays.

The deeper he dug, the more uncomfortable the situation got, so he reached out to the kindergarten and first grade teachers to get some insight into their reading instruction techniques.

“At the private school I knew that the children were already reading by the age of five, but here at the public schools the kindergarten teacher told me that they did not teach reading yet,” he says. He was shocked to learn their alternative was to teach children one letter per week, so began integrating some of the techniques he’d learned at the private school to help students catch up.

These discoveries prompted Rodriguez to go back to school to attain a certificate in elementary education, with an emphasis on English learners and special education students. As he learned more about these cases, he was reminded of his own childhood, the Civil Rights Movement, and the legal changes that came with it—laws that were supposed to set high standards for students regardless of who they were.

During the next 11 years, Rodriguez would see the benefits and shortcomings of these policies while teaching elementary school in Texas’ Edgewood Independent School District. For example, prior to the 2002 No Child Left Behind (NCLB), English learners (ELs), and Special Needs children were exempt from taking achievement tests. Rodriguez used to see the impact of that exemption during the school’s assessment days.

“I used to see so many kids wandering the halls during testing time, so I would pull them aside and I’d say, ‘hey, I noticed that you weren’t taking the test, what’s going on?” he recalls.

Students would say it was because they were in special education classes – but many weren’t actually receiving special education services. Jose notes, “That raised a lot of red flags. Lo and behold, I came to find out these kids were being labeled special ed so that their testing scores wouldn’t be reflected in the scores of the state,” says Rodriguez. “Despite federal mandates, students were still being tracked.”

Eager to help schools differentiate between children with disabilities and the needs of English learners, and help students with one or the other or both, he spent the next 10 years working as an education associate for the Intercultural Development Research Association (IDRA) to prepare teachers, parents, and administrators to better serve the EL population including the Special Needs ESL students, and to prepare for school visits from the Texas Education Agency or the Office of Civil Rights.

No Child Left Behind: Counting Students In

Jose saw the challenges facing Spanish-speaking parents (like his own mother and father) during the next few years at Judson ISD, where he assessed English Learner students and placed them in the appropriate program. He noticed that more students were being placed into middle school English language programs, and parents opting out of English as a Second Language services or bilingual education for their children. Under the Texas Education law, parents can deny such programs to their children, and many parents of ELs were indeed pulling them out.

The reason? Parents weren’t getting what they needed to make informed decisions, Rodriguez says. In fact, many feared their children would lose the ability to communicate with them.

“The parents sometimes don’t understand why we have the system, so we always tell them ‘your kids are going to learn English whether you like it or not, and they’re going to learn it fast. We’re teaching them in Spanish because that is the language they understand, but we’re also teaching them in English, and, as the English increases, we decrease the Spanish. At the end, they’re going to be bilingual.”

At the same time, Rodriguez found many ELs weren’t being identified as such until beyond kindergarten, or they were being misidentified as having learning disabilities, while those with true learning disabilities weren’t getting properly assessed to receive necessary accommodations from the school system.

“They kept being promoted until they couldn’t graduate from high school because they couldn’t pass the state test,” Rodriguez recalls.

Liaising between parents and through policy discussions has allowed Rodriguez to change scenarios like these. He reflects that he was able to do more to support English learners by advocating for policy change and implementation than he could have as a classroom teacher. As he became familiar with federal education laws, he was able to harness them for advocacy and planning.

Equal Assessment Standards for All

Federal civil rights laws have affected every part of Rodriguez’s experience in the education system. In 2000, Rodriguez was able to utilize Title VII federal grant money to obtain a master’s in bilingual education. A year after starting the program, the administration of George W. Bush reauthorized ESEA into the No Child Left Behind Act, which required states to develop their own standards and skills assessment programs. Now all students grades 3-12 would be regularly tested in math and reading.

“That’s why we have the expectation that even special education kids must be assessed, and their scores have to count as well,” he says, explaining that it’s not enough to just “test” all students. Rules and procedures must be put in place for how to test them. For example: “you have special kids who are non-verbal and we have to give them a verbal test, so you have to sit there until they either nod, they blink, they raise a finger.”

Every Student Succeeds Act

A lifetime of experience as an English learner, teacher, administrator, and advocate for families came together in 2013 when Rodriguez joined the UnidosUS’s education team to lead its family engagement work. As the director of Padres Comprometidos, he has been training parents and schools how to communicate plan their children’s experience in yet another era of civil rights legislation.

In 2015, two years after beginning these trainings, ESEA (the original civil rights education law) was reauthorized as the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). ESSA returned some local control to the states, and made the outcomes of English Learners more critical for federal funding. It took nearly three years for the federal government to approve all state ESSA plans, and the public discussion around these policies continues to be heated.

In Florida, for example, the state tried to create a dual grading system, separating performance data of more vulnerable students such as ELs or children with disabilities from the overall school rating. Civil rights advocates say this makes it hard for parents to know how schools are providing support for some of the students who need it most. They are also pushing for native language assessment tests, making it easier to know a student’s true knowledge base in all subjects, regardless of English proficiency. Meanwhile Arizona’s House of Representatives just approved UnidosUS-sponsored legislation aimed at repealing English-only teaching policies on the premise that these students fall behind in their studies because they are forced to reach English proficiency first.

Looking back, Looking forward

Amid all these new changes to federal education policy, and an uptick in xenophobia and racism, Rodriguez knows policymakers, teachers, and parents need to step up their efforts at making school a safe, healthy learning environment.

“When I was director of ESL and I’d get a new student, one of the first things on my agenda was ‘let’s go meet the principal,’” Rodriguez says. From there, he’d talk to school administrators about where this student is from and what they like to do. If it was soccer, the next step would be to get the kid talking to the coach, while a child with a musical background would quickly be moved into a music class, and so on and so forth.

This gave students a boost in confidence, while gently reminding teachers and school administrators of the young person’s equal right to a quality education.

“The kids felt included right away in the classroom, which in turn, led to better performance,“ he says.

-UnidosUS Senior Director of Teaching and Learning María Moser contributed to this report.